CORRECTION: This report was updated on May 22, 2018, due to the possibility that the language used to identify the German news outlet Die Tageszeitung may have confused respondents. References to that outlet have been removed throughout. There were no substantive changes to the report’s conclusions.

In Western Europe, public views of the news media are divided by populist leanings – more than left-right political positions – according to a new Pew Research Center public opinion survey conducted in Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

In Western Europe, public views of the news media are divided by populist leanings – more than left-right political positions – according to a new Pew Research Center public opinion survey conducted in Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Across all eight countries, those who hold populist views value and trust the news media less, and they also give the media lower marks for coverage of major issues, such as immigration, the economy and crime.1

Trust in the news media dips lowest in Spain, France, the UK and Italy, with roughly a quarter of people with populist views in each country expressing confidence in the news media. By contrast, those without populist leanings are 8 to 31 percentage points more likely to at least somewhat trust the news media across the countries surveyed.

In Spain, Germany and Sweden, public trust in the media also divides along the left-right ideological spectrum, but the magnitude of difference pales in comparison to the divides between those with and without populist leanings.

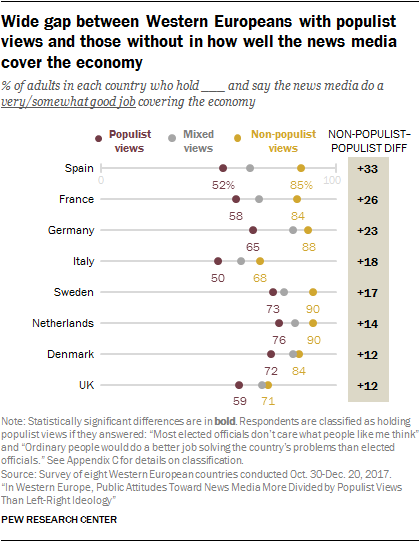

When it comes to how the news media perform on key functions, broad majorities of the publics rate the news media highly for generally covering the most important issues of the day. This includes majorities of both those who do and do not hold populist views, though there are still significant differences in the magnitude of those ratings. More substantial divides between those two groups occur around how the news media do in covering three specific issues asked about here: the economy, immigration and crime. (See detailed tables for more information.)

To evaluate the impact of populist views on attitudes about the news media in eight Western European countries, the survey focused on measuring core components of populism: that government should reflect the will of “the people” and that “the people” and “elites” are opposing, antagonistic groups. The measure is based on combining respondents’ answers to two questions: 1) ordinary people would do a better job/do no better solving the country’s problems than elected officials and 2) most elected officials care/don’t care what people like me think.

In examining differences based on these views, the report refers to people who hold “populist,” “non-populist” and “mixed” views. Those who answered that elected officials don’t care about people like them and who say ordinary people would do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials are considered to hold populist views. People who say the reverse – that elected officials care and that ordinary people would do no better – are considered to not hold populist views. Everyone else, including people who refuse to answer one or both questions, is considered to hold mixed views.

The reason for focusing on these core components of populism is that they cut across populist movements on the left and the right of the ideological spectrum. By having a measure that is not constrained by left-right ideology, the survey provides a consistent, cross-national measure of some fundamental tenets of populism. This measure of populist views is correlated with higher levels of support for both right- and left-wing populist parties.

For more information on this measure, see Appendix C.

People who embrace populist views express much less satisfaction with news coverage of these issues. In Spain, for example, those with populist leanings are 33 percentage points less likely than those without such leanings to rate the news media’s coverage of the economy as good. And in Germany, people with populist views are 29 to 31 percentage points less likely to applaud the news media’s coverage of immigration and crime than people who do not hold populist views.

People who embrace populist views express much less satisfaction with news coverage of these issues. In Spain, for example, those with populist leanings are 33 percentage points less likely than those without such leanings to rate the news media’s coverage of the economy as good. And in Germany, people with populist views are 29 to 31 percentage points less likely to applaud the news media’s coverage of immigration and crime than people who do not hold populist views.

In addition to within country differences, public attitudes toward the news media also diverge along regional lines. This is most evident when it comes to trust in the media, with public confidence considerably higher in the northern European countries polled, as opposed to the southern countries.2 The UK is somewhat anomalous, resembling southern, more than northern, Europe in its low level of public trust in the media (32%).

In addition to within country differences, public attitudes toward the news media also diverge along regional lines. This is most evident when it comes to trust in the media, with public confidence considerably higher in the northern European countries polled, as opposed to the southern countries.2 The UK is somewhat anomalous, resembling southern, more than northern, Europe in its low level of public trust in the media (32%).

And while majorities in all eight countries say the news media are at least somewhat important to the functioning of society, there are large differences among the countries in the portions who say that their role is very important.

In a question asked in a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults about trust in information from national news organizations, Americans display similar levels of trust as those in the Netherlands and Germany. About seven-in-ten Americans (72%) say they trust the information they get from national news media at least somewhat, with 20% saying they trust it lot.

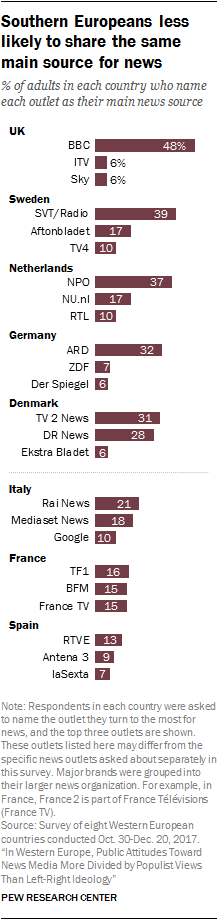

Despite the fact that people with populist views are much less satisfied and trusting of the news media, they often rely on the same primary source for news as those without populist views. This is the case in five of the eight countries surveyed: Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain and the UK. In four of these five countries, a single news provider dominates as the main source for news.

Despite the fact that people with populist views are much less satisfied and trusting of the news media, they often rely on the same primary source for news as those without populist views. This is the case in five of the eight countries surveyed: Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain and the UK. In four of these five countries, a single news provider dominates as the main source for news.

In southern Europe, the media landscape is more fragmented, with no single news provider named as the main news source by more than 21% of adults. It is also the case that in this part of Europe, left-right political identity is more aligned with people’s choice of main news source than their populist leanings.

In Italy, for example, 27% of those on the left turn to national broadcaster Rai News as their main source for news, compared with just 14% of those on the right. Italians on the right (30%) are more likely to turn to private broadcaster Mediaset News than left-aligned adults (6%). While there are some differences by populist views in Italy, the divide tends to be smaller when compared with those along the left-right political spectrum.

Here again the UK stands apart. Even as the BBC dominates as the top main news source for British adults –by both populists and non-populists – there is still a large difference between the portions of these two groups who name it as their primary source. Just 42% of those with populist views name the BBC as their main news source, compared with six-in-ten among those who do not hold populist views. Left-right ideological differences do not emerge: roughly half on both the left (48%) and the right (51%) name the BBC as their main news source.

These are some of the key findings of a major Pew Research Center survey of 16,114 adults about news media usage and attitudes across eight Western European countries – Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom – conducted from Oct. 30 to Dec. 20, 2017. Together, these eight European Union member states3 account for roughly 69% of the EU population and 75% of the EU economy.

Publics in Western Europe view news outlets as more partisan than what is reflected in their audiences

In each country, in addition to volunteering their main news source, respondents were asked about eight specific news outlets. These were selected by researchers to capture a range of news platforms, outlets with different funding sources, and diversity in their ideological leanings. Generally, people tend to describe outlets that they turn to for news as being relatively close to their own left-right political identity.4

This differs, however, from where the average audience actually sits politically. When asked whether people regularly turned to each of the eight outlets for news, the self-reported audiences of those outlets tend to cluster around the ideological center.

The goal for selecting news outlets for this survey was to ask about a list of well-known outlets that capture the broad range of news platforms in each country, which included outlets with diverse funding sources (public or private) and political appeal. Because of questionnaire length and the fact that the survey is administered over the telephone, we were limited to eight outlets that we could ask about in each country.

To choose these outlets, researchers used audience data and self-reported usage data to generate a list of the top outlets per country. From this list, we selected outlets that represented a range of platforms and funding sources, with a preference for more widely used outlets within these categories. Finally, we consulted media experts, reviewed academic studies and conducted focus groups in order to ensure that our selected outlets appealed to people across a wide range of political orientations. In certain cases, these consultations and focus groups led us to add smaller outlets to our list in order to capture the scope and variety of the media landscape in each country.

By asking about eight outlets that vary across four key factors — audience size, type of platform, funding structure and political appeal — we are able to capture public views about the broad scope of each country’s news media system. It is important to keep in mind, however, that a list of eight outlets cannot adequately represent the nuances of and full variety within the media landscape of any country.

For more information on this, see Appendix A.

In general, people who have heard of the outlets tend to place them either farther to the left or farther to the right than the self-reported audience results, showing that perceptions of polarization exist in the countries surveyed even though the audience figures reveal smaller divides.

Take, for example, the French private TV channel TF1. As shown in the accompanying graphic, TF1’s audience – those who say they rely on it regularly for news – is at about the middle of the left-right continuum (3.3 on the 0-to-6 scale.) Yet, when people in France who have heard of TF1 are asked to place it on the same left-right scale, they place it significantly farther to the right (at 4.1).

Many Western Europeans get news through social media, with Facebook being used most often

In seven of the eight countries polled, a third or more of adults get news at least daily from social media. The share that does so is highest in Italy, where half of adults get news daily via social media. In France, Spain, Italy and Germany, people with populist leanings are more likely to report getting news from social media platforms than those without such views.

Across all eight countries, Facebook is by far the most-frequently mentioned social media news source. More than 60% of social media news consumers in each country name Facebook as the social media platform they turn to most often for news. In some countries, Facebook is named as the main source for news overall by roughly 5% of adults, such as 6% of Italians and 5% of Spaniards.

Given recent concern about misinformation online, it is worthwhile to note that social media news consumers are not always discerning about their sources of news and information.

Given recent concern about misinformation online, it is worthwhile to note that social media news consumers are not always discerning about their sources of news and information.

Although most social media news consumers in Western Europe say they are familiar with the news sources they encounter, sizable minorities in each country say they don’t pay attention to where news on Facebook or other social media platforms comes from. The share of those who say they do not pay attention is roughly three-in-ten or more in France (35%), the Netherlands (34%), Italy (32%) and the UK (29%).

Further, whether or not the news seen on social media comes from sources people vet, few describe the news they see on social media as mostly aligned with their own political views.

Country-specific dynamics of the news media in the UK

Country-specific dynamics of the news media in the UK

The UK stands out as unique from the patterns we see in the other seven countries studied. On one hand, British adults are the most likely to have a common news source: 48% say the BBC is their main source for news. This level of clustering around a single main news source is similar to the other northern countries surveyed, such as Sweden or the Netherlands.

On the other hand, the British express low levels of trust and approval of their news media overall, similar to what the survey finds in the three southern countries surveyed (Italy, Spain and France). Just 32% of adults in the UK say they trust the news media at least somewhat, and roughly half or fewer say their news media do a good job of getting the facts right (48%), provide coverage independent of corporate influence (46%), or are politically neutral in their news coverage (37%). And when it comes to outlets besides the BBC, there are notable left-right political divides in usage. The magnitude of those differences in the UK looks similar to what occurs in the more ideologically divided southern countries studied.